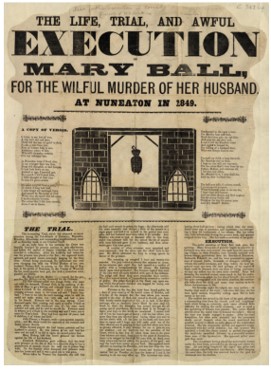

It is a quirk of the English language that pictures are hung (in a gallery) while people are hanged (from the gallows). Mary Ball was the last person to be hanged in Coventry UK. She denied poisoning her husband, but the jury found her guilty. However, having heard evidence of her ill treatment by her father and her violent husband, they asked the judge to imprison her rather than send her to the gallows.

The judge was having none of it, re-directed the jury to find her guilty of wilful murder, and sentenced her to death. Aged just 31, she was hanged before a huge crowd in an era when public hangings were a form of entertainment. However, many reported that they regretted attending, and public hanging in England was soon outlawed.

A vigil for her was planned outside the old prison in Coventry for the 9th August This is not now going ahead, but in lieu some people might like to read the story a friend of mine, Margaret Mather, wrote about her tragic life. This was published in an anthology in, Coventry Tales, in 2011, and is still available on Amazon books: https://mybook.to/CoventryTales.

Margaret has kindly given me permission to reproduce her story here.

GALLOWS DAY

“Mary Ball, you have been found guilty of wilful murder. You poisoned your husband, Thomas Ball, by administering arsenic to him. You will be taken to a place of execution where you will be hanged by the neck until you are dead. This will take place tomorrow, the ninth day of August 1849 at 10 o’clock in Pepper lane, Coventry. Do you have anything to say?”

“No sir,” Mary whispered.

“Take the prisoner down. The judge stood up, took the black cloth from his head and placed it on the table. Without a backward glance he left the room.

Mary was half dragged, sobbing, to the cells. Two burly prison guards opened the door and unceremoniously threw her in. She heard the ominous grating of a key turn in the rusty lock and the gleeful voices of the prison guards as they stumbled up the dimly lit corridor.

“It should be a right good hanging. Twenty thousand people I’ve heard tell are coming to see her drop.”

“Many are coming from her home town, Nuneaton. People from Bedworth have already started walking. There’s nothing they like better than a good hanging.”

“They say it’s to be the last ever female public hanging in Coventry.”

“Aye, John, everyone will want to be a part of that.”

“I’m taking the wife and kids. What about you, Will?”

“Wouldn’t miss it for the world. Food’s already packed.”

Their voices drifted away until all that could be heard were faint murmurings.

The room smelt of rotting cabbage; it was filthy and the stub of a candle stood in the middle of a wooden table. Straw covered the stone floor. Mary didn’t take much notice of her surroundings. Her head felt as if it would burst as she tried to take in the enormity of the position she found herself in.

How had it come to this? At the age of 31, here she was in prison, condemned for a crime she did not commit. Who would look after her daughter? What was to become of her? She was only 4 years old. The only thing left for her now would be the workhouse, and Mary cursed the day she had caught the eye of the girl’s father.

She lay down on the cold stone floor and tried to get some sleep. She must have drifted off, and woke with a start to find a man dressed in black shaking her roughly by the shoulders.

“Wake up you stupid girl, wake up,” he shouted in her ear.

Mary rubbed the sleep from her eyes and, as she became more aware, noticed that the candle was alight and two chairs were placed at the table. The candle threw long shadows into the corners of the small cell. A shiver ran through her and she began to shake uncontrollably.

“Mary Ball, I am the prison chaplain and I’ve come to ask you to put your mark on this confession.”

Mary was startled. “Why do you want a signed confession, I have already been found guilty.”

“You have professed your innocence all through your trial. I need a proper confession, one that will show how right we were to hang you. Now make your mark upon this paper, girl, and be quick about it.” The chaplain handed her a quill.

“I can’t do that, sir, I did not poison my husband.”

“Well now, that’s a great pity because I need a confession and I can guarantee that before sun rises I shall have it.”

Mary wasn’t sure how he would do that, but she had heard some gruesome stories about the torture that went on in these places. The tone of his voice terrified her and she knew that whatever he had in mind wouldn’t be pleasant.

“Come over here, girl; sit on that chair.”

Mary did as he ordered.

He sat opposite her. His dark eyes seemed to probe into her soul. She could smell ale on his breath, and gave an involuntary shiver.

“Now give me your hand.”

She did as asked. His grip was as hard as iron. Reaching for the candle, he pulled it close and at the same time lifted her hand in the air. Mary could tell by the speed of his hand that he had done this many times before. The candle was placed directly under her arm. She could feel the heat and tried to pull away, but he tightened his grip. Her flesh started to bubble and a smell akin to burnt pork reached her nostrils as a searing pain ran through her body.

She screamed. He carried on burning her flesh over the naked flame, oblivious to her cries of pain.

“Please let go of my arm, I beg you sir,” she pleaded.

He grinned at her. “Confess and I’ll stop. You have nothing left to lose.”

She knew he was right,

“Please stop, and after you have listened to my sorry tale, I will make my mark.”

“Carry on, I have all night,” he sneered, releasing his grip on her arm.

Mary quickly pulled her arm back. Blisters had started to form and they were hellishly painful. She was not going to let it show and in a quiet, dignified voice, she began to tell him about the events that led up to this horrific moment.

“I was the daughter of Isaac Wright and Alice Ward. My father was the innkeeper of the White Hart Inn, Market Square, Nuneaton. My mother died in childbirth.

“Blaming me for my mother’s death, my father made sure that I would cook, clean and wait on tables from an early age. I had to endure the sly touches from his customers when he wasn’t looking, the beatings for lying when I told him what they had done, and the awful loneliness. He never married again but plenty of women shared his bed.

“He would make me sleep in the kitchen with the dogs and woe betides if I ventured upstairs for any reason other than to clean. I wanted to escape this life, and when Thomas Ball told my father he would take me off his hands for a small fee, he agreed, and I thought anything would be better than this life of drudgery.

“I was wrong. Thomas Ball took great delight in using me as a punch bag. Even when I was nine months pregnant he would take his belt to me in one of his drunken rages. I lost five babies due to his beatings. I began to think I would never have any children. Then, when I was eight months pregnant with my last child, my father took seriously ill. He insisted that I move back in for a month or so to look after him and he bribed Thomas with a free glass or two of ale every night. That gave me just enough time for my daughter to be born without the constant threat of beatings.

“She was a beautiful baby, but it wasn’t long before the beatings started again, and when he had punched me senseless he would turn his attention to our daughter. I tried my best to protect her. At the start of one of my husband’s rages I would send Mary Ann outside to play in the street. It was safer there than back in her own home.”

Mary looked up into the face of the prison chaplain and thought she saw pity there, as if he realised she was someone who had been greatly mistreated by everyone she had ever come into contact with. He looked ashamed now of his torture, but Mary guessed he would soon be justifying himself by thinking that if he hadn’t done it, someone else would have.

“I hated my husband, loathed him with every breath that I took. I wished him dead many, many times but kill him, no, I didn’t kill him – he killed himself.

“Yes, I bought the arsenic from the chemist in Market Square and yes, I sat the bottle in the mantelshelf, but it was to kill bugs. I always put it high up, out of reach from my daughter. Thomas came home late; he was drunk and smelt of perfume from his latest woman. I had never seen him so drunk. He fell asleep on the chair and I went to bed happy in the knowledge that at least for one night my daughter and I would be safe.

“When I awoke the next morning, I found Thomas lying on the floor clutching a blue glass bottle. In his drunken stupor he had picked it up, believing it to be stomach salts. I took the bottle from his hand and hid it in my apron before sending for the doctor, because I knew I’d get the blame.

“Everything would have been fine, if someone hadn’t decided to tell the police that I had been heard in the street shouting at him ‘I’ll do for you!’ They decided on a post-mortem and, analysing his stomach contents, found more than the usual amount of arsenic.

“All my life I have fought so desperately hard, but when I heard the knock on the door and opened it to find the police standing there, I knew right there and then that my life was over. I would never see my daughter again.

“The only thing I can do for her now is to go to my death with grace and dignity.” The tears poured down her cheeks as she lifted her eyes and looked into the face of her tormenter.

“I believe you Mary, but I cannot do anything about it. I can, however, promise you that I will find a kindly family to look after your daughter and that she will be well cared for.”

“Thank you, sir. That’s all I can hope for.” Mary made her mark on the paper.

The day of the execution was sunny with a slight breeze; ideal hanging weather. The roads from Nuneaton and Bedworth were full of men, women and children, some riding, some walking. Laughter and music filled the air and a real gala day atmosphere was everywhere. There were pedlars on every street corner selling their wares; the smell of hog roast and fresh bread filled the nostrils as you passed. People were placing bets on how long it would take Mary to die. The Golden Cross had never been so busy. They couldn’t fill the jugs quickly enough.

Mary had walked the floor of her cell all night and, although exhausted, she knew it wouldn’t be long before she could leave this cruel world behind. In a resigned fashion she longed for 10 o’clock to come, when the noose would be placed around her neck and all of her past pain would disappear. She could hear the laughter and the music from the crowd outside and hoped she didn’t disappoint. Her only regret – Mary Ann, her daughter.

The prison chaplain entered Mary’s cell along with two guards. He found it difficult to look at her after listening to her story last night. The guards shackled her arms and legs with heavy chains.

“Please sir, what will happen to my body after I’m dead? Will there be a headstone for my grave?” The chaplain looked at Mary and, with almost a hint of pity in his voice, he said,

“I’m sorry but your body will be buried upright in an unmarked grave, underneath the cobbles, beyond the grounds of Holy Trinity Church. All murderers must be buried upright so that they may never rest in peace. A death mask will be cast of your face and will be placed on a pole for everyone to look at in quiet contemplation. There will be no headstone.”

It was a short walk from the goal to the gallows in Pepper Lane. Mary summoned from deep within all of the strength and dignity needed to see her through the next ten minutes. As she stepped up to the gallows, there was a hush from the huge crowd. They held their breath; the rope was placed over her head and the trapdoor opened. Mary’s body jerked once or twice like a puppet on strings and then stopped.

The crowd erupted.

*********