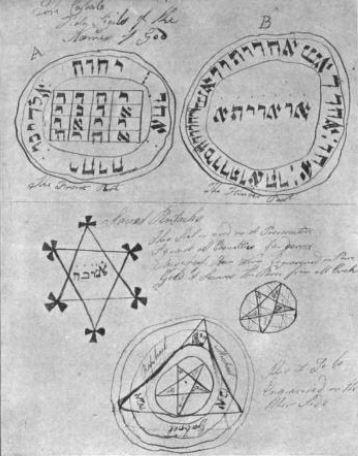

A late 18th-century Magic Book

I’ve been reading and thinking a good deal about 18th century Cunning-Folk. The first discovery I’ve made is simple: I knew a great deal less about who Cunning-Folk were and what they did than I thought I knew.

What made someone part of the group of local, ‘alternative’ practitioners known as Cunning-Folk? Where did they get their power and authority? What did they believe about themselves? More importantly, what did their clients and the people amongst whom they moved believe about them? What did they even do? Were they all quacks and charlatans; little more than confidence tricksters or stage magicians, who preyed on people’s gullibility?

These are some of the questions I’m going to try to answer in a series of blogs during the coming months include:

- Who were these Cunning-Folk? How did you gain this reputation?

- What did they do for people?

- What cultural beliefs and context allowed them to operate?

- How did they relate to the orthodox medical practitioners of the time?

- How did they fit into what was supposedly an overwhelmingly Christian country?

- How did they differ from witches and warlocks — always supposing they did?

I’ve already featured a Cunning Woman in my two most recent Ashmole Foxe Mysteries. She’s in “Bad Blood Will Out” and she also appears in the following book, “Black as She’s Painted”. However, neither delves deeply into her activities. In one sense, this is fair. What I have discovered suggests that the ‘high tide’ of the Cunning-Folk occurred during the 16th and 17th centuries, with a slow decline thereafter, as an increasing emphasis on rationality and science replaced mystical and supernatural explanations of natural phenomena.

The Cunning-Folk may have faded from our lives, but they never went away entirely. The more I discover about them and their activities, the more similar much of it appears to today’s booming industry in alternative medicine and life-styles. Orthodox medicine and state interventions may have triumphed on the surface. Look more closely, however, and you could argue that the Cunning-Folk are having the last laugh!

In that vein, here’s an excerpt from the “Norfolk Chronicle” for Saturday, 1st April 1815:

At the trial of Lucy Black, for robbing Robt. James, the following peculiar circumstances were detailed. The prisoner, it appeared, was the grand-daughter of the prosecutor’s wife, and resided with the prosecutor. The whole family went to the meeting house on the March instant, but the prisoner not being quite ready, did not go with the prosecutor, but remained in the house herself, and arrived at the meeting-house, which was at a considerable distance, within a few minutes after the prosecutor. On their return home, the prisoner observed to the prosecutor, that she saw a light in his dwelling, which was then above mile distant. The prosecutor also, saw a light, but could not discern at what house. When they got home, they found two squares of the outside window broken, as if for the purpose of getting in a hand open the casement, and a briar bush under the window was partly cut away and much trampled down. Upon entering the house they found the things scattered about, chest broken open, guineas missing thereout. A very extraordinary stratagem of the prisoner led to the suspicion of her having committed this robbery, during short time that she remained in the house after the prosecutor was gone to the meeting-house. She related to her grandmother shortly after, that she had been to the cunning woman, Lucy, who had told her that the bigger half of the money would be returned the next day, at about the same hour that it was stolen. At about eight o’clock on the following evening, the prisoner said she heard a noise and went into the garden to make out what it was. Shortly afterwards, she returned, and said she saw somebody in a dark coat fly over the garden gate, upon which the prosecutor went out to see this extraordinary sight. He did not see the dark coated Genius, but the prisoner took this opportunity for picking up a paper parcel at the door containing eleven guineas, which she took to her grandmother, observing that the fortune-teller’s prediction had come true.