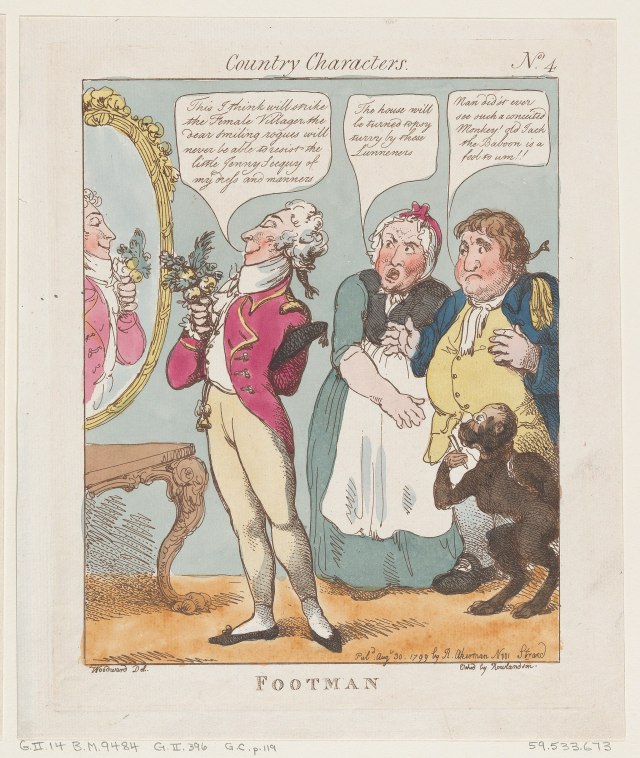

This is a follow-up to my earlier article about the problems of managing servants in the 18th-century, with particular reference to the diaries of Gertrude Savile. It focuses on events in July, 1756, and concerns her footman, John Barlow, and the havoc that one male in a household of three females (four, if you count Gertrude herself) can bring about.

We begin on July 6th, when Barlow had a quarrel with one of the maids, Sarah. Afterwards, she went to her mistress and told her a long tale of what had been going on in the household behind her back. Gertrude had obviously been quite taken with Barlow herself, since she records that, in the course of the year, she had given him a livery coat and waistcoat, three “frocks” and two more waistcoats. She had also, she said shown, “forbearance and kindness to him in his sickness.” This seems to have been a series of epileptic fits.

Now, however, she reproaches herself for having kept him on, despite recording that he abused, cursed and threatened her. Why did she do it? Perhaps the catty nature of some of her remarks throughout the record of the incident gives us a clue. Barlow must certainly have had something, since it appears that all three of the maids were under his spell. Even Gertrude herself refers to him at one point, perhaps sarcastically, as “the Adonis John Barlow”. She then writes:

“I was silly enough to think him a sober and modest fellow but he was far otherwise, a scandalous whoremaster; made quite a brothel of my house with one if not two of my maids. There is little doubt of Ann Jennings being his strumpet, old, ugly and demure as she was; she, I suppose, bought his favours. He charmed the housemaid also, so that (I am since convinced) her jealousy was the cause of her letting me know the scandalous affairs long transacted in my little family.”

Even when she was sacking him, Gertrude gave him one of his new “frocks”, his waistcoats and a hat, whether from fear or liking she does not record. What she does say is that he “haunted the house every day” for a time, supposedly to ask her to give him a character, but actually to try to get what he could from the maids. She says that she was so terrified and miserable she had to get the coachman to stay as much of the day as he could and asleep in the house overnight.

More Trouble

This went on for most of the month, until, at the end, she sacked Ann Jennings:

“… a woman more vile than her paramour. She must have bribed the young fellow to make a whore of her. Made? No: she must have been so before. What victuals, beer, wine, candles, soap, coals, everything but what they might by law be hanged for, was given out of my house. I am amazed at my stupidity to let such doings continue, but all my four servants hanging together, and my lameness, made them secure from my detection.”

On the 30th, she sacked the cook, of whom she wrote:

“I thought it was impossible she could be amorously disposed and be such a beast in her dress, though young and pretty. I often in jest said to her, ‘Sure you have no sweetheart; you would not be such a slut if you had’.”

She continued to employ the housemaid who had informed on Barlow, despite being “sick of the same distemper”, after she had dismissed the others. Meanwhile, she replaced both her personal maid and cook, and hired a new footman called William. None of them lasted a year in her service.

Reality versus Hollywood (and Television)

All this took place in London, and I cannot help wondering whether she would have found it such an easy matter to replace her servants had she been living outside the capital. Perhaps, if she had known in advance that she could not easily replace any whom she dismissed, or who left of their own accord, she would have taken greater care to try to keep those whom she found most acceptable. Perhaps not. I know of at least one case in Norfolk in which the mistress of the house had at least as much trouble with servants as did Gertrude; though that case occurred almost a hundred years later. While it’s obvious from the diary that Gertrude Savile was difficult, demanding and often downright bitchy, there is nothing to suggest that her situation was altogether unusual.

As I said in my first post on this subject, too many of our notions about life in grand households during the 18th and 19th centuries come from costume dramas. There everything from the cleanliness and politeness of the servants to their generally good behaviour has been passed through the sanitising and romanticising lens of television and film. Gertrude’s picture of lazy, deceitful, lustful and larcenous servants makes a good corrective. It is also probably somewhat closer to the truth.

Savile, Gertrude, et al. Secret Comment: The Diaries of Gertrude Savile, 1721-1757 . Devon: Kingsbridge History Society; [Nottingham]: Thoroton Society of Nottinghamshire, 1997.