How the collapse of a Norwich cloth merchant through rash over-expansion and foreign adventures helped trigger the decline of the trade in Norwich “Stuffs” (fine worsted fabrics), which was further accelerated by changing technology and new materials.

Philip Stannard was born in Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk, on 6th December, 1703. His father was a member of the prosperous merchant community of Bury and must have expected his eldest son to follow in his footsteps when he apprenticed him to an experienced master weaver in Norwich in 1719. The Norwich textile industry already had an excellent reputation and the man to whom young Philip was apprenticed was a trader in cloth, as well as a manufacturer. The training lasted for seven years and in 1726 Philip Stannard was able to establish himself as a Freeman of the city of Norwich and begin trading on his own account.

Like most Norwich cloth merchants, his cloth was produced by individual journeyman weavers, working at looms in their own homes. Stannard bought the thread for them to use, sent it to a dyer to be dyed in the correct colours, and paid them for producing cloth to his order. Payment was on a strictly piece-work basis. After that, much of the cloth would have been hot-pressed: a process which gave the surface a fine, glossy sheen. Norwich was famous for producing cloth with the most intricate weaves, often mixing fine wool with silk or linen to give greater strength or greater softness. Much of it was highly coloured and highly patterned and in the early to middle part of the eighteenth century it was both highly fashionable and much sought-after.

Stannard obviously prospered. In 1732 he was able to buy his own house in Norwich, which he insured for the considerable sum of £500 (around £200,000 in today’s money). By 1748, he had moved to a much larger house which he insured for four times as much. He also seems to have bought a number of small houses in the neighbouring parish, probably to house his weavers, eventually adding to these until he owned a whole series of tenements along Fisher Lane to Pottergate. He also inherited his father’s house in Bury St Edmunds when his father died in 1747 and seems to have kept that as an investment property.

Like many a successful merchant before and after him, he now decided he was wealthy enough to become a country gentleman and purchased a mansion some five miles outside the city. This was close enough to allow him to maintain supervision of his business on a daily basis at the same time as enjoying his new property, with its eight acres of grounds and pleasure gardens. He also took on a partner, Philip Taylor, to run things on a daily basis and the business became Stannard & Taylor. There was soon a third, junior partner, John Taxtor, whose name was never added to the business, but who played a significant part in its progress towards collapse. In 1762, Stannard’s young second wife presented him with a son and, in 1765, a daughter. All seemed set fair.

Decline and Fall

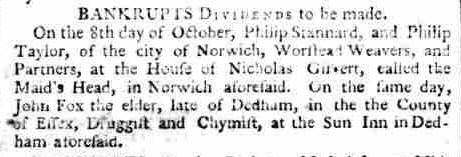

Within four years, the firm of Stannard & Taylor had collapsed into bankruptcy owing the amazing sum of £47,000 (around £10-12 million in today’s money). What went wrong?

Cloth manufacturing and selling is a business that depends heavily on fashion. All the Norwich cloth merchant experienced considerable ups and downs in business. However, since the Norwich firms supplied cloth to order, they were usually able to respond quickly to varying tastes, as well as moving to exploit the growing overseas markets. In nearly all cases, their sales were handled through middlemen in London and it was these middlemen who bore most of the risk, especially in the case of overseas sales. Once completed, the orders of cloth would be loaded onto trains of pack horses and sent to London, where local agents would handle the business of delivery and collection of payment.

Stannard’s business was no different, save in being rather more extensive than many. In 1755, he was able to boast that he was keeping three hundred weavers in constant work. For a business of the time, this was an astonishing claim. A few dozen workers would have represented a substantial operation at a time when all supervision was personal and communications either face-to-face or by letter, which would take days to arrive at its destination (weeks if sent overseas). Besides, producing the heavily patterned, lustrous weaves typical of Norwich cloth was a complex and difficult process and might be spoiled at any point. Perhaps because of this, in 1762 Stannard set up his own fully-equipped hot pressing shop and was able to boast to his customers that he had all aspects of the manufacture under his own control. In modern jargon, he was making his business ‘vertically-integrated’.

It was also at around this time that the firm seems to have begun doing business directly with foreign buyers. Many Norwich cloth merchants were tempted along these lines, hoping to be able to obtain greater profits by removing the amounts which had to be paid to the London middlemen. In doing so, of course, they had to assume all the risks that they had avoided before that time. Not only might shipments be lost at sea, which could be covered by insurance, foreign purchasers were often slow-payers. In 1759, Stannard himself had told a correspondent that he refused to consider dealing in any other way than via London middlemen. What changed his mind is not clear, but the better question might be “who?”

We don’t know whether it was a desire for greater profit or the influence of one of his younger partners or employees which caused him to agree to send his business in a new direction. He might have been influenced by the ending of war with Spain and the consequent opening up of European and South American markets. He might have been influenced by the actions of many of his competitors in also seeking to increase direct overseas trade. He might have realised his home market was under threat from cheap imports of printed cottons and calicoes from the far east. Whatever it was, he was clearly unprepared for the amount of risk that he was now taking on. Like many a business before and since, Stannard & Taylor was about to expand overseas without the strong capital basis required to do so. Stannard might have been a fine weaver and an honest trader, but he was much less capable as a businessman venturing into difficult waters.

John Taxtor seems to have been particularly active in the early 1760s in pursuing overseas markets. He may well have been behind Stannrd & Taylor’s sudden appetite for entrepreneurial ventures. From what is known of him, he was a born salesman with all the strengths and weaknesses that that implies. Even when he first joined the firm, he brought Stannard & Taylor a number of direct contacts amongst overseas buyers, as well as a taste for fresh ventures and new ideas. He visited Germany several times, where he claimed to have received considerable orders, and certainly picked up a number of fresh designs which were quickly put into manufacture and claimed as Stannard & Taylor inventions. However, his greatest enthusiasm was for exports to Spain. Indeed, in the middle of the century the firm had to increase the size of its warehouses and other buildings in Norwich to allow for the extra production demanded by the Spanish orders he was obtaining.

Since Philip Stannard had now reached his early sixties, it looks as if he was leaving most of the running of his business to his younger partners. It must therefore have been a terrible tragedy for the firm when John Taxtor suddenly died, aged 39, in 1766. The business struggled on, but it became increasingly difficult to obtain funds from those merchants in Spain who had bought their cloth. The business had also started sending cloth to South America on a purely speculative basis, rather than supplying it to order. When the firm crashed, nearly all the payments for this cloth were still owing.

Disaster!

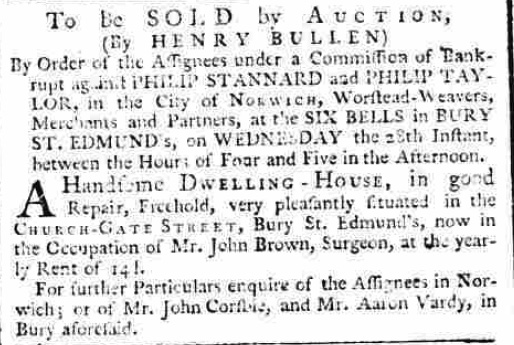

Stannard & Taylor were declared bankrupt in 1769. All the property of the remaining partners, including Stannard’s fine country mansion, had to be sold. Even then, the creditors received only a very small proportion of the debts owed to them. The city of Norwich was hit hard, with many weavers put out of work and many investors and suppliers badly out of pocket. As modern times have shown many times, the failure of a large business always causes a large number of associated failures, sometimes affecting more people than the original bankruptcy itself.

Unfortunately, this crash coincided with other problems for the cities once-prosperous cloth merchants. The use of home-based weavers was rapidly being overtaken by factories using the latest machinery, much of it water powered. Since Norfolk lacks the fast flowing streams necessary to drive the new machinery, the trade moved away, principally to Yorkshire. When steam replaced water as the source of power, the Yorkshire mills could easily be supplied with coal from local mines, where all coal had to be brought in from outside to factories based in Norfolk. To this was added a change of fashion, away from wool towards printed cottons, first imported from India and then produced on a massive scale in the Lancashire cotton mills. The day of the Norfolk cloth manufacturers was over. Some weaving and dyeing remained into the nineteenth century, but on a much smaller scale and devoted mostly to specialist markets, such as black bombazine for mourning clothes and the production of highly patterned shawls.

Doesn’t all this sound depressingly familiar?

The first book in my series of Ashmole Foxe Georgian Mysteries, “The Fabric of Murder” is based very loosely on the same idea of the bankruptcy and collapse of a major cloth manufacturer in Norwich and the damage to the city it was feared that would cause. Click here to find out more.