How long have you been writing or when did you start?

I tried to write my own stories since I began buying my own books in elementary school through the monthly Scholastic Book Club. Back then, though, I didn’t comprehend fully how stories began, were built, and ended, so I wrote a lot of beginnings that just slowly withered away without meaning or story. Dark Shadows on TV was not only a huge influence on me, but the novels were as well, and Dark Shadows was equally a powerful force to 1960s/’70s popular culture. My first stories were Dark Shadows stories, but they never got beyond an opening description of the weather at Collinwood. The influence of Dark Shadows—small towns, abandoned houses, mysterious woods, old graveyards, and vampires—was a driving impulse through the writing of Ghostflowers.

I wrote my first completed story—a time travel epic that was completely forgettable—when I was twelve on my father’s manual typewriter. I sent it off to Galaxy Magazine, and it was rejected a year later. I shrugged it off and kept writing anyway. My first published novel, Spelljammer: The Ultimate Helm, was written when I was 33/34 and living in Orlando, and published in 1993. But I have been writing professionally since 1983, starting out selling articles to a local alt-weekly newspaper, writing movie and theater reviews for two local papers, and then freelancing to national magazines such as Omni and Premiere. After Spelljammer was published pseudonymously, the D&D people also published my two novels in their Endless Quest series, Castle of the Undead and Dungeon of Fear in 1994, which were also published under pseudonyms. Then 1996 was a creative year for me. My novella, “Puppy Love Land,” was published in the Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, and later it made the preliminary ballot for Best Novella for the Horror Writers Association awards.

Are there any books or authors that inspired you to become a writer?

Honestly, every fictional tv show that I loved, every comic book, every short story, every novel influenced me to become a writer. Dark Shadows was my first serious influence; but the novels of Edgar Rice Burroughs were the driving force that convinced me I could be a writer. I joined Doubleday’s Science Fiction Book Club, and one of the first books I bought, A Princess of Mars with its stunning, unforgettable cover painting by Frank Frazetta, just slammed me. Burroughs somehow made an impossible story about a Civil War veteran on an alien planet seem 100% believable…and with each Burroughs book I bought, I realized that I could write stories like that, too. Then Stephen King came along, and I talked with him at a couple of World Fantasy Cons early on, and his down home, casual air of being a normal person who told extraordinary stories showed me that a guy like me could write professionally. Still in college, at the ’79 World Fantasy Con in Providence, I stood at the top of a staircase at the convention hotel, surrounded by books and ideas and fantastic worlds, and I realized that writing novels for a living was all I ever wanted to do. In later years, I learned a great amount just watching the first season of Twin Peaks, so I suppose David Lynch taught me a lot about mystery and the powers of both stillness and silence.

Do you have any suggestions to help me become a better writer?

You bet your ass I do.

1. Read everything.

2. Watch movies—a LOT of them—and learn about structure and timing. You’ll also learn a lot about clichés and tropes, and why you should avoid them.

3. Don’t be afraid to read bad books along with good. Sometimes the worst books will show you what not to do in your own fiction.

4. Grammar and spelling are vitally important to being a good writer. Good enough is not good enough. Be the best.

5. Don’t write in a vacuum. When you first start out, do not depend on your own critical faculties to tell you if your own writing is good or bad. You can’t depend on yourself in this case, because you’re too close to the material and can’t be objective (and usually, neither can your family members).

I strongly urge that you take college level workshops, where a group reads your stories and gives you honest, critical input. While attending Old Dominion University, I was lucky enough to go through intensive writing workshops with novelist Tony Ardizzone. He introduced us to a highly critical workshop structure that influences me even now, more than forty years later.

Every week we’d take home one writer’s story, read it, and mark it up, asking questions, giving our opinions, and being 100% honest with our appraisals of the work. The next week, we’d all sit around in a circle and give both specific and general comments about the story in question. Here’s the most important thing: The writer was not allowed to speak. At all. (The idea was that when a novel is published and put out in the world, it gets reviewed and critically appraised, and the author is usually unable to respond, at least in a timely or immediate fashion. Nowadays, the Internet has changed all that, but it’s still a great idea for writers to never respond to negative criticism.) The point was for the writer to absorb the comments, and to face an ultimate fact: if someone has a comment about any aspect of a story, then the writer must look at the story and ask themself What is going on here? Did I make a mistake? Is the critic responding to something I intended or for some other reason? A mistake I made? Could I write this part clearer? What did I do here that made someone question it? For instance, Tony Ardizzone once told the class about a story of his—a baseball story. A comment he received from one reader was that the story was really a love story, and that he didn’t need the baseball aspect at all. Tony went back and reread what he had written—and he added more baseball to the story. He realized that the reader’s opinion wasn’t necessarily correct, and, more importantly, that the reader had really discovered an aspect that was lacking. Adding more baseball made the story better—and whole.

A workshop environment such as the one I experienced could be absolutely brutal. But it was absolutely vital to my growth as a writer.

How long did it take you to write this book…or any other book?

My wife gave me the idea for Ghostflowers one morning while I was shaving, getting ready for work. By the time I’d finished shaving, I knew who the primary characters were and the main thrust of the novel. That was 1996. I wrote the first four chapters and an outline and sent them to my agent. This was at a time when published writers could write a portion of a novel and actually get it bought by a publisher…depending. In my case, I hadn’t published enough for an incomplete novel to be bought.

So, real life eventually got in the way of my writing career. We moved a few times, and I got a few different jobs. After finishing an unpublished fantasy novel about adventure pulp fiction, The Enigma Club, I realized it was time to get back to Ghostflowers. I’m most comfortable writing from rough outlines, so I re-outlined Ghostflowers and started in on it seriously in 2013. I finished the first draft in 2014, did a few rewrites and polishes, wrote a detailed outline and a concise outline, and started sending out query letters in 2016. So it really took me about a year and a half, while I was working at my day job, to finish the first draft.

While this was at a time when vampire fiction was hot because of the Twilight series, paranormal romances were on the way out, and agents had grown tired of seeing vampire novels despite their continued popularity with the reading public. I’m not one to be dissuaded in the face of negativity, and I really don’t like taking “No” for an answer. So I kept sending out query after query. Someone once said that the successful writers are the ones who persevere. I persevered and queried more than 300 agents until I found the perfect agent to take me on. Ghostflowers was acquired by JournalStone Publishing in January 2021, and published July 2022. The published novel is the 13th draft.

I also got the idea for The Enigma Club in 1996. I was reading all the Edgar Rice Burroughs Tarzan novels that I hadn’t read when I was young—books 11 through 24—and I thought I’d write a satire of the old adventure pulps starring a Tarzan-esque, clueless jungle guy—think Forrest Gump of the Apes. I created a back story for him, and placed him on a mysterious island…and suddenly the island itself became more important to me than my jungle king. I visualized a brownstone located on the island: a club for all the heroes and adventurers from 1930s pulp adventure tales, and an island where the pulps were still alive—and The Enigma Club came to life. That stayed in the notebook stage until about 2003, when I started the first draft, and I remember working on the finished draft on a plane heading for Hawaii in 2005. That novel’s in the trunk for now, but I think I’ll bring it out again in the future. I’m considering using the characters and the locale for a fictional podcast.

My first three novels were works for hire published by Dungeons and Dragons, and they took thirteen, ten and nine weeks to write, respectively.

What comes first for you—the plot or the characters—and why?

Every novel is different. Ghostflowers sprang into my mind, characters and important beats already born. Some of their names changed—actually, Summer’s name changed. When I originally thought of her, she was named Cassandra. Then I found out that Cassandra was the name of a main character in an existing series of vampire novels—I don’t remember the name of the series, though—and I decided to change it. So I thought about what a character’s name should be who embodied the endless spirit of summer…and what else could it be but Summer? So Cassandra became her middle name.

The Enigma Club presented more of an intellectual exercise at first: Who would populate the Enigma Club? I realized it was the archetypes from both the end of the Golden Age of Adventure and the explorers and adventurers from pulp fiction. At the same time, my subconscious told me the club building was in ruins—I mean, there’s something mysterious and evocative about ivy-shrouded ruins, isn’t there? So a bare bones story developed, about an anonymous character who goes on a quest to find this island and this club in the present day—and he discovers his quest is not only to bring the Enigma Club back to its former glory, but to uncover its link to his father. I learned a long time ago not to make things up, like most people think writers do, but to listen to my subconscious and to figure out what the puzzle really is, and how to fit the pieces together. The Enigma Club was a huge puzzle for me to write—it wouldn’t even let me outline it in my usual fashion. Ordinarily, I outline a novel several times, always building upon what I outlined earlier. But The Enigma Club would only let me outline the next chapter after I finished writing the previous chapter. It was truly a novel of self-discovery.

How much research did you need to do for your book?

Verisimilitude. Verisimilitude is the over-reaching concept of how to make the unbelievable believable. That’s probably the most important word to remember when you’re writing any novel, but especially in the realm of speculative fiction, and particularly one that takes place in the recent past: because some of your readers lived through it, you have to get that era right. So I had to time travel back to the summer of ’71, and properly evoke the era in the reader’s mind. I hope I achieved it.

My research was intense and ongoing for years, especially during the writing of the first draft. I went to microfiches of the daily papers for 1971 to check the major headlines and to see what movies were playing. Scars of Dracula and Horror of Frankenstein were playing at one of my hometown drive-ins the weekend of July 4th, so I placed the double feature at the drive-in theatre in Ghostflowers, and they were perfectly appropriate. I went to YouTube to watch trailers for movies that played in June and July ’71, and for the cartoons that hawked the concession stands at drive-ins during intermission. I researched the songs that would have been on the radio that weekend, and focused on a lot of songs that I remembered, but also what Summer and her friends would have been listening to, and I realized I had to narrow my timeframe, or I’d have to mention every song from the sixties to June ’71. For names, I turned to phone books for Hampton/Newport News, Virginia and for Richmond, and collected first and last names that sounded both vintage and Southern. While I was working at the Caroline Progress in 2011, an older woman named Ruthette came in to pay her subscription, and I thought her name was so beautiful and unique and so Southern that I made sure to save Ruthette for the name of an important character. I also researched the children’s park that’s a locale in Ghostflowers, and found my memories jogged of my own childhood visits to Story Book Land in northern Virginia (https://tinyurl.com/55nxsvxr). I had to know about the motorcycle Michel rides, and where he served in Vietnam, and how and where he came back to the states (LAX). I had to find out what perfumes Summer would wear. I had to find out if Maker’s Mark was being produced in ’71, and if the Virginia ABC stores carried it. I even researched the nightly tv shows that would be on by looking up July ‘71 issues of TV Guide online.

In short, I did everything I could to make sure I was transporting the reader to an accurate representation of Virginia in 1971—but, more importantly, I had to evoke the feeling of being there: the way the teenagers then wore their clothes, what the rhythm of their language sounded like, the smells you’d experience in a diner, or on the road, surrounded by woods and newly-mown grass. The stench of the sheriff’s Pall Malls. The aroma of Summer’s blonde hair. The smell of Ruthette’s vintage pomade. Research alone serves some historical value, but its true purpose in fiction, I believe, is to help evoke the appropriate emotional responses in the reader’s heart, and to evoke a sense of a particular place and time. Verisimilitude.

At what point do you think someone should call themselves a writer?

Some people are not going to like my answer.

Anyone can call themselves a writer. I remember speaking with Harlan Ellison about a gentleman he knew: a lifelong writer who had never once been published. Harlan shrugged (and I’m paraphrasing here). “He’s a writer. He writes. That’s what he does. But I don’t think you’re a real writer until you’re a published writer.”

I have to agree with Harlan’s more candid comment. You need a work—preferably a body of work—for those times people ask, “And what do you do?” and you say, “I’m a writer,” and they respond with, “Have I ready anything you’ve written?” What are you going to say? The point is, you can’t be a writer unless you can prove it, and I suggest that to call yourself a writer, you have to be a published writer. Preferably, to call yourself a writer, you should be professionally published: you’ve sold pieces to magazines, or a novel or a nonfiction book to a publisher, and, most importantly, they have paid you to publish your work.

I have been a professional writer since 1983, and only last year, for the first and, I hope, only times, I wrote two articles that I was not paid for by a publisher. I did this deliberately: one piece was to promote Ghostflowers (https://www.mysteryandsuspense.com/blood-moon/) and the other was for a unique fanzine of particular interest to me, which is still unpublished.

Writers not only need to write—to write often, and to write well—but to make a living at it.

To be a professionally, writers should expect to be treated professionally—and to demand it. Don’t write for free. Don’t be an amateur. If you’re a writer, you should always act like a pro.

Do you play music when you write—and, if so, what’s your favorite?

Music—specifically classic rock—was integral to the telling of Ghostflowers, and I even posted on YouTube a playlist of songs mentioned in the novel. (https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLdPkP5ontMSQG9lVjvSYsTmK2fUvOLwqI)

My own tastes are a little bit different than those of my characters. I love the Blues, and Blues/Rock fusion, some ‘70s classic rock, and almost anything by Jimmy Buffett (favorite Buffett tune: “Blue Heaven Rendezvous,” about a wonderful restaurant in my favorite place, Key West.) But I discovered a long time ago that I can’t listen to that kind of music when I’m writing, because I get into the music too much. It’s so alive. It just takes over, and I can’t concentrate on what I’m writing.

What really helps when I’m writing is soundtrack music, especially epic, sweeping scores, such as the themes on the album Moviola by John Barry, which I listened to repeatedly while writing The Enigma Club. I wrote Ghostflowers in longhand first, mostly while at my desk at my day job, and there was no music playing in the store, so I streamed instrumental soundtracks on my laptop through channels on iTunes. That could be hit or miss for me, because they’d occasionally play music that I simply couldn’t stand—such as overly-frenetic cartoon music—and I found myself changing stations all too often. But, when I’m at the keyboard, give me John Barry and Jerry Goldsmith and John Williams all day long.

What would you say to an author who wanted to design their own cover?

IN THE NAME OF ALL THAT IS HOLY, DON’T DO IT.

Okay, now that I let that out, let’s talk.

I know that a lot of writers want to self-publish. Self-publishing also means that they get to design their own covers.

You remember the old saying about lawyers?

“A lawyer who represents himself has a fool for a client.”

Cover design entails a lot of things: art designing the front cover, spine and back cover; finding artwork and perhaps even paying to use it; manipulating the art; choosing fonts for the title, subtitle, author’s name, the spine, and the copy on both the front and back. There’s more. A lot more. But the idea with a book cover is to create the first thing the reader sees: it’s the impetus for readers to pick up the book in the first place. I consider the cover to be a silent commercial. It has to lure a consumer toward it, and then sell them right there on the spot.

Publishers have designers and copywriters who have trained for years in marketing. They know what works with copy, the same way that the writers and editors of movie trailers know how to get you interested in a film a year before it shows up in theaters. Yet almost every self-published writer I know truly believes themselves equal to or better than professional artists, designers and marketers when it comes to their own books.

Unless you have an art degree; unless you have years of experience with PhotoShop and InDesign; unless you have experience writing promotional copy; unless you have extensive experience doing compositional layouts designed to influence consumers—DON’T DESIGN THE COVER YOURSELF.

Most publishers don’t consult the writer when designing their covers. They let the writer’s book speak for itself, and their assigned teams determine the book’s audience, and then choose a designer to reach their publishing goals. The author rarely, if ever, has a say in cover design—and, given that most writers have little to no expertise in the mechanics of marketing and graphic design, I actually think that’s smart.

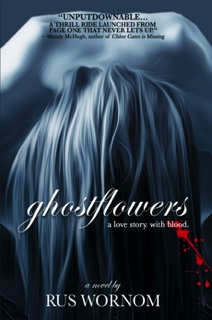

Ghostflowers was different. The publisher is JournalStone, and they have a limited budget for cover design. The editor usually asks writers what they hope to see on the cover of their books; and in my case, I asked for the cover to be a faux, 1971-era movie poster for Ghostflowers. I drew up an initial layout, based on a vintage ’71 drive-in movie poster, and sent it on; but we couldn’t get a good cover produced in the right amount of time. I then hustled, found some nice royalty-free art that a graphic designer closely cropped and manipulated in PhotoShop; I wrote the copy, chose the blurb for the front cover, and selected the fonts.

Why could I do all this when I tell you not to do any of it? Because I’ve had an eighteen-year career writing promotional copy for advertising and marketing clients, also while designing ads for print, audio and tv, designing books, booklets and marketing publications, flyers, media kits, and hundreds of multimedia presentations—and I’ve also won awards for my efforts. AND I have an art degree.

With the rise of desktop publishing, we are today experiencing an onslaught of novels and story collections that have not been professionally curated, professionally copyedited, nor professionally designed.

It’s an age of amateurs, and many self-published writers don’t know what they don’t know.

This is a Dunning-Kruger situation for some creatives.

Remember: A bad cover, like poor editing, bad spelling, and incorrect grammar, will have a negative impact on sales. All covers are reflective—intrinsically connected to the novel itself; and an awful cover will imply that the novel itself is awful.

Don’t have a fool for a client. Always be the most professional writer possible. If you’re going to take control of your books and self-publish, spend a little money. Buy book covers from artists who do this daily—you can find a bunch of them on Twitter, some of whom will sell you a pre-designed cover for only about $25. Find books with jacket copy that you admire, then copy the ways the copy has impact, and how the verbiage represents the book inside the covers. Learn what fonts to use—and especially the fonts you shouldn’t use. (I mean, I liked Papyrus, too, when it was released decades ago, but its overuse on signage and menus has completely killed its impact.)

Even better: Hire a pro to do it all for you.

If your book were made into a movie, which actors would play your characters?

I’ll give you two casts. First, let’s take a deep dive and assume they’re making this movie during the time period it portrays. Ghostflowers would have been the perfect, summertime, R-rated drive-in movie for 1971. Sexy heroine; macho motorcycle man; evil sheriff; wicked mother; an illicit party in the woods; some rednecks and fighting; rocket-fast muscle cars; rock and roll; vampires and bloodletting and nudity and some underground cave sex— Yow! This movie has everything a sweaty, hormonal, drive-in audience would want! So, I’d cast Playboy “sexpot” Claudia Jennings as Summer Moore, James Brolin (with a thick, Fu Manchu moustache) as Michel, chain-smoking Forrest Tucker as Sheriff Hicks, and Agnes Moorehead as Summer’s mother. For ‘71, their looks are quintessential.

This cinematic vision is B-movie, hixploitation heaven!

Today, however, character actors seem to be in short supply. Most of the cast needs to look Southern—to a degree—and their looks need to fit the characters’ personalities. Summer Moore needs to be beautiful, but in a girl-next-door way, and not too exotic-looking, so I’d consider actresses such as Hunter King, Katherine McNamara or models Deanna Ritter or Cathlin Ulrichsen. Michel needs to be dark and European-looking—someone like Kit Harrington. The sheriff needs to be grey-haired with a crewcut, a little grizzled, and he definitely has a redneck Southern accent. I’d love to see Alec Baldwin, Hugh Jackman or Jeff Bridges as Sheriff Hicks—if they could nail the accent—and Bridges would have to lose the facial hair. And I think it would be awesome if we could get the quintessential victim of ‘70s horror, Carrie herself, to play against type and take on the role of the overbearing, evil mother. Sissy Spacek, I think, would be perfect!

AUTHOR BIOGRAPHY (if needed)

Rus Wornom is a Southerner who loves to gaze at the soft haze between the trees on lazy summer days in Virginia while his pups play around him. His new novel, Ghostflowers, is a supernatural Southern gothic with a 1971 classic rock background. “The whole story sprang to life one morning while I was getting ready for work, when my wife gave me a crazy, awful idea for a novel—and it took me over. Within minutes I knew the characters’ names, I knew almost everything that would happen, and I knew that the main characters would not, could not, live happily ever after. One had to die.”

Wornom’s 1996 novella, “Puppy Love Land,” was nominated for an award from the Horror Writers Association in 1997 (preliminary ballot). He graduated from Old Dominion University with a B.A. in Art, and attended the University of Miami Graduate School for Creative Writing. He lives in central Virginia with his long-suffering yet devoted wife and his spoiled pets, and was born and raised in Hampton, VA.

Amazon Link: https://amzn.to/3xY4yx1

Website: ruswornom.com

Facebook: Facebook.com/ruswornom

LinkedIn: www.linkedin.com/in/ruswornom

Threads: ruswornom@threads.net